This memorial arch is made from hand hewn coal taken from the entrance to the Mt Kembla mine.

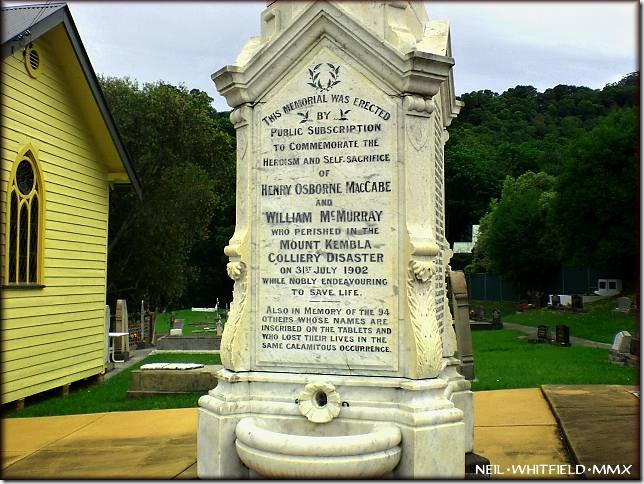

An explosion at 2pm on July 31, 1902, at Mt. Kembla colliery killed 96 men and boys. The sound of the explosion could be heard in Wollongong, some 7 miles away. At the end of the day 33 women were widows and 120 children were fatherless.

The hundreds of rescuers were headed by former Keira Mine manager and ex-mayor of Wollongong, Major Henry MacCabe who had played a vital part in rescue efforts at the Bulli Mine disaster in 1887 which killed 81 miners.

MacCabe and Nightshift Deputy, William McMurray were to lose their own lives during the rescue effort to the effect of “overpowering fumes”, adding 2 more deaths to the 94 miners…

— See Mt Kembla Colliery

Chances are you’ve seen this. I was tagged by Lynne Sanders-Braithwaite. “Bold those books you’ve read in their entirety, italicize the ones you started but didn’t finish or of which you have read an excerpt and underline movies you have seen.”

1 Pride and Prejudice – Jane Austen

2 The Lord of the Rings – JRR Tolkien

3 Jane Eyre – Charlotte Bronte

4 Harry Potter series – JK Rowling

5 To Kill a Mockingbird – Harper Lee

6 The Bible

7 Wuthering Heights – Emily Bronte

8 Nineteen Eighty Four – George Orwell

9 His Dark Materials – Philip Pullman

10 Great Expectations – Charles Dickens

11 Little Women – Louisa M Alcott

12 Tess of the D’Urbervilles – Thomas Hardy

13 Catch 22 – Joseph Heller

14 Complete Works of Shakespeare – well, most of them!

15 Rebecca – Daphne Du Maurier

16 The Hobbit – JRR Tolkien

17 Birdsong – Sebastian Faulk

18 Catcher in the Rye – JD Salinger

19 The Time Traveler’s Wife – Audrey Niffenegger

20 Middlemarch – George Eliot

21 Gone With The Wind – Margaret Mitchell

22 The Great Gatsby – F Scott Fitzgerald

24 War and Peace – Leo Tolstoy

25 The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy – Douglas Adams

27 Crime and Punishment – Fyodor Dostoyevsky

28 Grapes of Wrath – John Steinbeck

29 Alice in Wonderland – Lewis Carroll

30 The Wind in the Willows – Kenneth Grahame

31 Anna Karenina – Leo Tolstoy

32 David Copperfield – Charles Dickens

33 Chronicles of Narnia – CS Lewis

34 Emma -Jane Austen

35 Persuasion – Jane Austen

36 The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe – CS Lewis

37 The Kite Runner – Khaled Hosseini

38 Captain Corelli’s Mandolin – Louis De Bernieres

39 Memoirs of a Geisha – Arthur Golden

40 Winnie the Pooh – A.A. Milne

41 Animal Farm – George Orwell

42 The Da Vinci Code – Dan Brown

43 One Hundred Years of Solitude – Gabriel Garcia Marquez –

44 A Prayer for Owen Meaney – John Irving

45 The Woman in White – Wilkie Collins

46 Anne of Green Gables – LM Montgomery

47 Far From The Madding Crowd – Thomas Hardy

48 The Handmaid’s Tale – Margaret Atwood

49 Lord of the Flies – William Golding

50 Atonement – Ian McEwan

51 Life of Pi – Yann Martel

52 Dune – Frank Herbert

53 Cold Comfort Farm – Stella Gibbons

54 Sense and Sensibility – Jane Austen

55 A Suitable Boy – Vikram Seth

56 The Shadow of the Wind – Carlos Ruiz Zafon

57 A Tale Of Two Cities – Charles Dickens

58 Brave New World – Aldous Huxley

59 The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time – Mark Haddon

60 Love In The Time Of Cholera – Gabriel Garcia Marquez

61 Of Mice and Men – John Steinbeck

62 Lolita – Vladimir Nabokov

63 The Secret History – Donna Tartt

64 The Lovely Bones – Alice Sebold

65 Count of Monte Cristo – Alexandre Dumas

66 On The Road – Jack Kerouac

67 Jude the Obscure – Thomas Hardy

68 Bridget Jones’s Diary – Helen Fielding

69 Midnight’s Children – Salman Rushdie

70 Moby Dick – Herman Melville

71 Oliver Twist – Charles Dickens

72 Dracula – Bram Stoker

73 The Secret Garden – Frances Hodgson Burnett

74 Notes From A Small Island – Bill Bryson

75 Ulysses – James Joyce

76 The Inferno – Dante

77 Swallows and Amazons – Arthur Ransome

78 Germinal – Emile Zola

79 Vanity Fair – William Makepeace Thackeray

80 Possession – AS Byatt

81 A Christmas Carol – Charles Dickens

82 Cloud Atlas – David Mitchell

83 The Color Purple – Alice Walker

84 The Remains of the Day – Kazuo Ishiguro

85 Madame Bovary – Gustave Flaubert

86 A Fine Balance – Rohinton Mistry

87 Charlotte’s Web – E.B. White

88 The Five People You Meet In Heaven – Mitch Albom

89 Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

90 The Faraway Tree Collection – Enid Blyton

91 Heart of Darkness – Joseph Conrad

92 The Little Prince – Antoine De Saint-Exupery

93 The Wasp Factory – Iain Banks

94 Watership Down – Richard Adams

95 A Confederacy of Dunces – John Kennedy Toole

96 A Town Like Alice – Nevil Shute

97 The Three Musketeers – Alexandre Dumas

98 Hamlet – William Shakespeare

99 Charlie and the Chocolate Factory – Roald Dahl

100 Les Miserables – Victor Hugo

He would have been 99.

It was also the 26th birthday of Australian cricketer Peter Siddle.

See Kersi Meher-Homji on The history and significance of a hat-trick.

Much has already been written on Australian pace bowler Peter Siddle’s hat-trick on the opening day of the Brisbane Test yesterday. But how many know about the origin of the term hat-trick?

This term first appeared in ‘The Sportsman’ (England) of 29 August 1878 when Australia’s celebrated bowler Fred ‘Demon’ Spofforth clean-bowled three batsmen with three consecutive balls, “thus accomplishing the hat-trick” when playing for the touring Australians against 18 of Hastings & Districts at The Oval.

He was also the first cricketer to claim a Test hat-trick against England four months later in Melbourne on 2 January 1879…

The five day game is the only real Cricket, isn’t it?

Preface

[added July 2011]

See the following posts leading to this one:

This is the article to appear in December’s South Sydney Herald. The blog and the SSH hardly overlap, hence this preview.

Mr Howard vs David Hicks

A friend of mine was in Pakistan at the same time as David Hicks, and in many of the same places: Peshawar, Quetta, Pakistani Kashmir. There’s even a photo of my friend in Pashtun costume holding an AK47. That was a joke photo taken in a Peshawar arms bazaar. My friend went east and met the Dalai Lama. David Hicks went west and met Osama Bin Laden. My friend came home much sooner.

When David Hicks memorably confronted John Howard on Q&A in October he asked two questions: was I treated humanely? and was the Military Commission process fair? Howard answered neither question, applying the airbrush liberally to what really happened to Hicks between 2001 and 2008.

After distracting us with a motherhood statement about what a great country we have to allow Hicks to bail him up like this, Howard spun first into irrelevance: “Now, having said that, can I simply say that I defend what my government did in relation to Iraq, in relation to the military commissions….” How did Iraq get into this?

He went on: “We put a lot of pressure on the Americans to accelerate the charges being brought against David Hicks and I remind the people watching this program that David Hicks did plead guilty to a series of offences and they, of course, involved him in full knowledge of what had happened on 11 September, attempting to return to Afghanistan and rejoin the people with whom he had trained. So let’s understand the reality of that David Hicks pleaded guilty to.”

TONY JONES: Mr Howard, on this question of him pleading guilty, Mr Hicks says in his own book that his military lawyer, David (sic) Mori, was told by your staff that Hicks wouldn’t be released from Guantanamo Bay unless he pleaded guilty. Was that your position?

JOHN HOWARD: Well, I’m not aware of any such exchange but, look, I mean, there been a lot of criticism of that book by sources quite unrelated to me and I’ve read some very, very severe criticisms of that book…

Howard’s late-blooming desire to see Hicks returned to Australia had everything to do with VP Cheney’s visit to Australia in February 2007, when the deal that led to Hicks’s “conviction” was stitched up, and behind that was the 2007 Election. Howard knew the issue was losing him votes.

Colonel Morris Davis, the prosecutor in the case, recalls that in January 2007 he received a call from his superior Jim Haynes asking him how quickly he could charge David Hicks. (Now an attorney for Chevron, Haynes had in 2005 told Davis: “Wait a minute, we can’t have acquittals. We’ve been holding these guys for years. How are we going to explain that? We’ve got to have convictions.”) David Hicks was eventually charged on 2 February 2007, even though the details about how the commissions should be conducted weren’t published until late April. (Interview Amy Goodman and Col. Morris Davis 16 July 2008.)

Davis resigned from the Military Commission after prosecuting David Hicks, stating that “what’s taking place now, I would call neither military or justice.”

Howard assured us that the US had a long tradition of Military Commissions. He failed to mention that this particular Commission had been struck down by the United States Supreme Court in the case of Hamden v Rumsfeld in June 2006 so that what David Hicks was dealing with was a reinvented version, but as much a kangaroo court, to quote a senior British judge, as the previous edition.

More airbrushing. And there’s more.

David Hicks’s guilty plea was an odd beast, an Alford Plea, something peculiar to US law. It is the plea of guilt you make when you don’t believe you are guilty but do believe the court is likely to find in favour of the prosecution. I may also add that David Hicks was never at any stage charged with or found guilty of terrorism. Some of the charges in Gitmo seem to have been invented specifically to justify the imprisonment of people there. Mr Howard passes over such technicalities.

Colin Powell’s former Chief of Staff, Colonel Lawrence Wilkerson, summed up his view of Guantanamo in an article published in November 2010.

…no intelligence of significance was gained from any of the detainees at Guantanamo Bay other than from the handful of undisputed ring leaders and their companions, clearly no more than a dozen or two of the detainees, and even their alleged contribution of hard, actionable intelligence is intensely disputed in the relevant communities such as intelligence and law enforcement. This is perhaps the most astounding truth of all, carefully masked by men such as Donald Rumsfeld and Richard Cheney in their loud rhetoric–continuing even now in the case of Cheney–about future attacks thwarted, resurgent terrorists, the indisputable need for torture and harsh interrogation and for secret prisons and places such as GITMO.

Curiously, one item in Hicks’s book that even he had doubts about has just been shown to be exactly as Hicks tells it: the existence at Guantanamo of a “Camp NO”, so called because it didn’t officially exist. Murders took place there, according to Marine Sergeant Joe Hickman (Harpers: “The Guantánamo ‘Suicides’: A Camp Delta sergeant blows the whistle.”)

Nearly 200 men remain imprisoned at Guantánamo. In June 2009, six months after Barack Obama took office, one of them, a thirty-one-year-old Yemeni named Muhammed Abdallah Salih, was found dead in his cell. The exact circumstances of his death, like those of the deaths of the three men from Alpha Block, remain uncertain.

Those charged with accounting for what happened—the prison command, the civilian and military investigative agencies, the Justice Department, and ultimately the attorney general himself—all face a choice between the rule of law and the expedience of political silence. Thus far, their choice has been unanimous.

Not everyone who is involved in this matter views it from a political perspective, of course. General Al-Zahrani grieves for his son, but at the end of a lengthy interview he paused and his thoughts turned elsewhere. “The truth is what matters,” he said. “They practiced every form of torture on my son and on many others as well. What was the result? What facts did they find? They found nothing. They learned nothing. They accomplished nothing.”

I have been reading Guantanamo: My Journey very carefully for around four weeks. I have also done a lot of fact checking. I especially recommend the report on David Hicks’s trial by Lex Lasry QC, available on the Internet, which includes the texts of all the charges and the final plea bargain. Hicks had a choice: stay in Gitmo or sign the admissions and go home. What would you do after more than five years? And no, Mr Howard, he was not treated humanely, and no, the system was eminently unfair.

Former Minister for Veterans’ Affairs Danna Vale (Liberal, Hughes) got it right as far back as November 2005:

… The longer Hicks is in Guantanamo Bay, his imprisonment without trial will begin to creep like an incongruent shadow, jarring the Australian consciousness

Let’s get real. The case of David Hicks clearly fails the commonsense test. It fails the commonsense test not only in the educated minds of the legal profession, but in the gut feelings of ordinary Australians who believe in a fair go, and who believe that truth and justice and that old hand-me-down from the Magna Carta that says men are innocent until proven guilty, still deserve some currency in our world. Just like you, just like me, as an Australian, he is entitled to a fair trial without further delay. And, after four years in Guantanamo Bay, if the Americans cannot deliver this to David Hicks, in all fairness, we must ask that he be sent home.

In one of the more considered reviews of David Hicks Guantanamo: My Journey (William Heinemann 2010) Sally Neighbour claims that Hicks has airbrushed some parts of his story. At least she has read the book. I too find it difficult to believe he first heard of Al Qaeda after his capture, but endorse his recommendation of Jason Burke’s Al-Qaeda: The True Story of Radical Islam as the best on the subject.

By contrast look at Miranda Devine’s recent review of Hicks’s book, a sustained sledge against Dick Smith who assisted financially with David’s defence. Beyond that she descends into emotive claptrap or sheer ignorance, the latter being her inability to believe Hicks became a Muslim by looking up a mosque in the yellow pages and then meeting an imam. She doesn’t seem to have mastered Islam 101: one can become a Muslim simply by repeating “There is no God but Allah and Muhammad is his prophet” to another Muslim. No course necessary. On this I absolutely believe Hicks, who, incidentally, no longer considers himself a Muslim.

One telling item for Hicks in the book is the famous picture of David with the rocket launcher. We all remember how this was used to demonise him and purported to show him in Afghanistan. It turns out to be cut from a photo taken in Albania of three friends playing around with empty weapons. Yes, he took part in the Kosovo war, but never saw action. Another photo shows him saluting the NATO flag, under which he was really serving then.

Guantanamo: My Journey is a book we need to read. I am glad it has been published. Like Sally Neighbour, there are some things I would like clarified, but I now believe it to be mostly truthful. Hicks was a bit of a fool, you know, even if a desire to aid oppressed people is quite commendable in itself. He was after all a 20-something at the time, and “under-researched” as he now says. He hasn’t killed anyone or engaged in any act of terrorism; everyone admits that.

One of the most valuable features of Guantanamo: My Journey is the extensive footnotes, a marvellously detailed documentation of the material in the book. I wish they had been set in their places at the bottoms of relevant pages rather than being gathered in the back. The book also desperately needs a thorough index.

David was pretty much a pawn. Heroes? Well, I’d nominate David’s father, and Major Michael Mori, his defending counsel, whose career after that suffered. (See The Marine Corps News 20 September 2010.)

PS: not in the article

David Hicks is accurate in his depiction of the Tablighi. I know this because I have taught one and did considerable research about Tablighi Jamaat at the time. With regard to Lashkar-I Taiba, Hicks may have polished the image somewhat, but it is fair to say that what he says about that organisation in the areas he found them may well have been true at that time and place. The organisation was not yet a listed terrorist organisation in Australia. Certainly David’s depiction of the Taliban is much less admiring in the book than it was in his letters home as seen in the documentary The President versus David Hicks. On the other hand Hicks’s explanation about his letters reflecting what he was seeing and reading at the time in the Pakistani press may well be true. It is also notable that Terry Hicks seems to take David’s rhetoric in those letters with something of a grain of salt. The book leaves no doubt about what David feels about the Taliban now. His account of the training he received in Afghanistan and Pakistan may be true but I do have some doubts about this.

Miranda Devine’s characterisation of David’s account of Guantanamo as “whingeing” is quite outrageous. Says more about her than it does about him.

My spellings reflect usage in The Oxford Dictionary of Islam.

Capturing life's moments, one frame at a time

[two new poems added every day]

Adventures in a historic landscape

Stories, Excerpts, Backroads

Just another WordPress.com site

Making you think

Family History

The silent camera

Just because you CAN read Moby Dick doesn't mean you should!

This WordPress.com site is the bee's knees

Reflection

Musings on poetry, language, perception, numbers, food, and anything else that slips through the cracks.

Movies, thoughts, thoughts about movies.

Selected Poems

#Strongwomen. "I write about the power of trying, because I want to be okay with failing. I write about generosity because I battle selfishness. I write about joy because I know sorrow. I write about faith because I almost lost mine, and I know what it is to be broken and in need of redemption. I write about gratitude because I am thankful - for all of it." Kristin Armstrong