Yes, the Proust project continues in fits and starts. I find I can travel over to Proustland and stay for several hours with enormous pleasure, then go elsewhere for a day or a month and return where I had left off to take on that special world once more. I am now into The Captive – so I have made progress since July. See Proust: visiting a demented relative? Thanks, Kobo – but it does mean I am reading via eBook the old Scott Moncrieff translation. See also: All about the new Penguin/Viking editions of Marcel Proust’s great novel, À la recherche du temps perdu, once known in English as Remembrance of Things Past but now more accurately titled In Search of Lost Time.

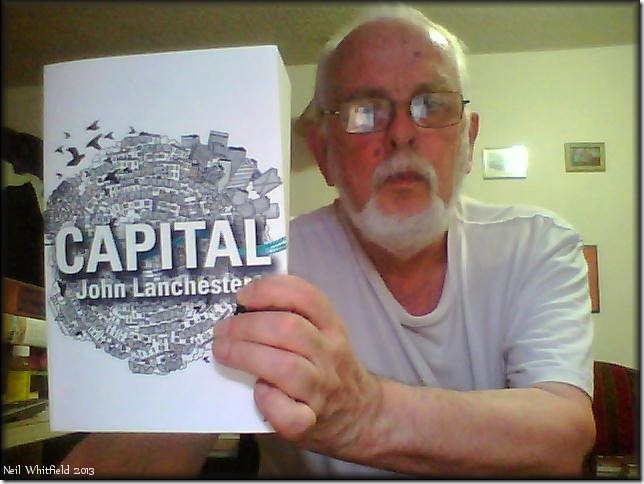

Loved John Lanchester’s Capital. From The New York Times review:

Lanchester, a brainy, pleasure-loving polymath, is a novelist, memoirist and journalist who writes sagely and elegantly about food, family, culture, technology and money. He’s still best known for his delectably wicked first novel, “The Debt to Pleasure,” which blends murder with gourmandise. But he has also written a well-reasoned nonfiction book entitled “I.O.U.: Why Everyone Owes Everyone and No One Can Pay,” which closely analyzes the current financial collapse. Now, with “Capital,” he readjusts his sights and zooms out, framing a larger, more inclusive picture that shows how the easy-money era affected not just greedy speculators but the society that fattened around them.

The fiction I am currently savouring is The Importance of Being Seven, the sixth collection of episodes set in Scotland Street, Edinburgh, by Alexander McCall Smith. I read the seventh one in December: Bertie Plays the Blues. But no matter that I am out of sequence; the delight is undimmed.

Non-fiction just now is A Wild History: Life and Death on the Victoria River Frontier by Darrell Lewis. Tom Griffiths on Inside.Org rates it one of the best (overlooked) books of 2012.

If Ned Kelly had been gentler and more learned but just as much a bushman he might have written A Wild History: Life and Death on the Victoria River Frontier (Monash University Publishing, $29.95). Darrell Lewis’s book is a distillation of bush wisdom and scholarly tenacity, of courageous fieldwork and equally adventurous archival sleuthing, of forty years of learning the country and of a lifetime of listening to history. Lewis has walked the Victoria River District in Australia’s northwest, swum its crocodile-infested rivers, got to know its plants, animals and people, slept under its stars, inspected its caves, recorded its inscriptions on rock and tree, and then pursued its material diaspora wherever it may have migrated. I am reminded of a great landmark work in Australian history, A Million Wild Acres, a book about the Pillaga Scrub by another bush scholar, Eric Rolls. Lewis’s book is full of frontier stories, superbly researched and skilfully told. And the book to look out for in early 2013 is The Archaeology of Australia’s Deserts (Cambridge University Press) by Mike Smith. It’s the most important work in Australian archaeology since John Mulvaney’s The Prehistory of Australia (1969).

See also John Rickard in The Australian Book Review:

The Victoria River District is unusual in its lack of family dynasties with roots in the pioneer generation. The early settlers, who were occupying vast tracts of land, tended eventually to sell up and return to something more like civilisation. Lewis puts this down to the harsh climate, and to the remoteness and isolation, which lacked the ameliorating influence usually provided by country towns. With the high turnover of station staff, there has been ‘a weak transmission of local knowledge’. The irony is that Aborigines, who, unlike the settlers, ‘don’t come from somewhere else, stay for a period and then leave’, are actually ‘the “keepers” of much “European” history’. Lewis knows the District’s Aboriginal communities well, and is able to draw on the perspective on European settlement of those who so fiercely resisted it.

Lewis stresses the sophistication of Aboriginal land use, particularly in the deployment of fire. ‘They knew that burning at the appropriate time would promote the flowering of certain plant species, and the growth of particular food plants, or would attract desirable animals to the burnt area, and they knew that if they burnt certain food plants in patches over time, the plants would fruit over an extended season.’ This seems consistent with the argument recently advanced by Bill Gammage in his prize-winning The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia (2011), which presumably was not available to Lewis when

he was writing A Wild History…At the heart of A Wild History, however, is a meticulous account of the halting progress of European settlement and the varied opposition it faced from the District’s thirteen or so Aboriginal peoples or language groups…

A Wild History is a fine piece of scholarship, exemplary in its judicious interpretation of both white and Aboriginal oral tradition, as well as the documentary sources. Just as the story begins with ‘the aura about the country’ firing Lewis’s imagination, so at the end it is the landscape, majestic, beautiful, forbidding, that has the last word. Keith Windschuttle could learn a lot from this book.

I doubt KW would, alas – but I have been finding the book quite a revelation.

from the cover of A Wild History

And then there is William James.

The Varieties of Religious Experience

A Study in Human Nature

William James

To

E.P.G.

IN FILIAL GRATITUDE AND LOVE

1902

Yes it is dated, but on the other hand what a great classic it is! Makes you wonder whether we really have learned a great deal that matters since 1902. I certainly am enjoying this very belated first acquaintance.